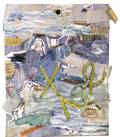

Vaigotas, 2023

Vaigotas is a word coined by my two-year-old daughter, Maria, used as a noun to name what the rest of us will call seagulls. Nothing new – an exchange of letters identical to so many others made by babies of the same age – and yet so full of intention.

The term “vaigotas” – like “gaivotas” (seagulls) – is a sound, with a written correspondence, intended to indicate certain seaside birds. However, the term “vaigotas” – like seagulls – has nothing objective about it, and its relation to the animal in question is just as valid in one case or another, as is the term “seagul”, “geasul” or “knee”. And yet, there isn’t a bird that passes by that doesn’t deserve a sharp point of the finger, followed by the vocative “vaigota”. Who am I to say that’s not a “vaigota” but rather a “gaivota”? Where do I get the certainty or authority to justify Maria’s correction? If she has so many certainties – and I have so many doubts – why can’t I adapt?

The question raised seems like a frivolous invitation to anarchy, but it is also, however, a alert to the lightness of our institutions: can’t those be “vaigotas”? Couldn’t we eat with our hands? Why do we wear clothes and why can’t we have everything we want?

The same applies to representations. What makes a simple elongated M less of a seagull than a naturalistic drawing? If this animal is caricatured and wears a hat on its head, will it be now something else or a seagull with a hat? How can we conceive of a seagull with a hat if we’ve never seen one?

From this reflection began the series of works that, following the usual modus operandi and formats, plays with these variants, proposing compositions that range from almost scientific representations to the most analytical, almost erroneous, proposals, covered in abstract or translucent layers that reinforce the shared fragility of words and images.